A Short History of the Iron Foundry in America: Early Republic

A Revolution in Iron Foundries

After the Revolutionary War a second “revolution” was awaiting the US iron foundry industry. Until the early 1800s, iron foundries used charcoal exclusively to heat the vats of molten iron. While other parts of the world were looking for other sources of fuel to replace wood, the United States had abundant amounts of that resource and little motivation to change. For the next fifty years and through another war with England, the American foundries maintained the same fuel source.

Changes Around the World

But changes were happening in the iron industry around the world. In England, the smelting of iron using coke made from coal was first introduced in 1709. This important innovation expanded the opportunities for the iron industry in England and parts of Europe but wasn’t as urgent of a technological advance in other countries. Coke is a fuel source created when coal is heated in the absence of oxygen and coal was far more plentiful in England than wood. The English and Scottish foundries saw this as an opportunity for their countries to gain more independence from the foundries in continental Europe. The continental foundries, such as in Sweden and Russia, had the advantage of more abundant natural resources such as wood and plentiful rivers.

The adoption of coke was slow in England. The first use of coke in an iron foundry by a successful business was in Coalbrookdale by Abraham Darby I. This encouraged others to work to build foundries to utilize this new technology. The primary focus was to produce bar iron using coke since bar iron could be used in the production of a variety of other ironware. Unfortunately, most of those businesses had little commercial success. That all changed in 1755 when Mr. Darby’s son, Abraham Darby II, and a few partners opened a new foundry in nearby Horsehay. Their commercial success in producing bar iron from a coke foundry was followed by others. But this new fuel source had the unfortunate result of making the iron more brittle than the finery forges wanted. The new iron was harder to work with, so the iron from the continent was still preferred by those who were crafting more detailed ironworks.

Innovation Leads To Innovation

This issue and the stimulation in the foundry industry in England led to further innovations. The primary innovations were in the reinvention of the iron foundry process itself. In the 1760s and 1770s a process that was known as “potting and stamping” was devised. This process involved melting pig iron, allowing it to cool, and then using a stamping method to break up the resulting iron. The iron was then washed and then reheated in large pots. This was done in reverberatory furnaces, which subjected the iron to the combustion of the gases from the oven’s fuel. The iron that was produced from this method was then drawn out under a forge (or trip) hammer. This process was slow to be adopted, but within fifteen years of its patent it was in use throughout the West Midlands of England.

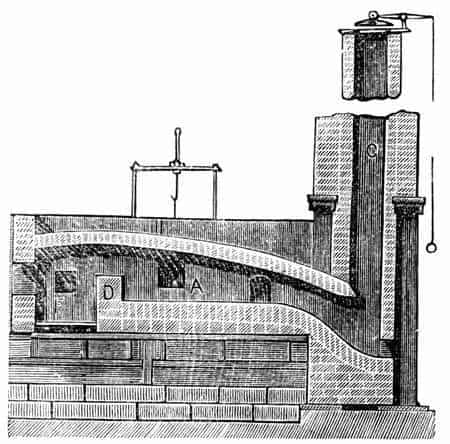

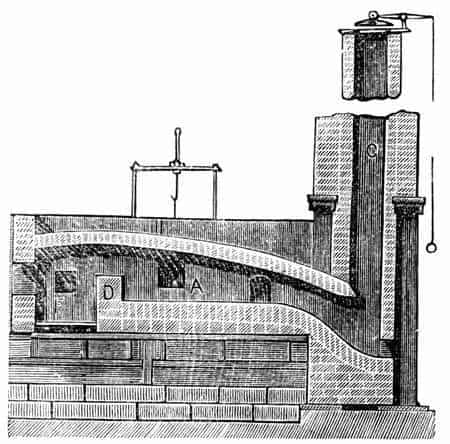

Schematic drawing of a puddling furnace

The next process innovation was more widely adopted and quickly replaced the potting and stamping process. Puddling furnaces used a process by which iron was refined by a series of steps involving slowly melting the iron as it is exposed to combustible gases that reflected off of the ceiling of the furnace down onto the iron. Then a strong air current was driven across it. As the air current runs overtop of it the mixture is stirred by puddling bars (or raddles). Puddling bars are long iron bars with hooks on the end that were used to not only stir the iron but to eventually form a “ball” of the iron that had puddled on the top of the heated metal.

The ball of puddled iron was pulled from the furnace by one man (called a “puddler”) and then transferred to another man (called a “shingler”). That man would then take the iron to the anvil of a “shingling” or trip hammer (eventually replaced by the steam hammer). The iron was then subjected to a rigorous pounding to force out the impurities and prepare it for the rolling mill. The rolling mill was the last step in the process, allowing the foundry workers to produce bar iron. The flattened iron was passed through rollers with increasingly smaller gaps until the desired size was achieved.

The Dark Side To Puddling Iron Foundries

This process produced iron that was well suited to the finery foundries’ needs. While it was effective in producing iron that was less brittle and easier to work with, the process was physically demanding and resisted technological improvement. This was because the process relied on the puddler’s ability to determine when the iron was ready to be pulled out and the puddled iron balls weighed up to 250-lbs. Additionally, the process exposed men to intense heat and fumes from the furnace. The strain from looking into the melting iron took its toll on the workers’ eyes. The strain from such work usually meant frequent injury and early death.

Transitioning Fuel Sources

These innovations revolutionized the iron industry in England and slowly made their way across the ocean to the United States. Remarkably, the process of innovation in the United States actually occurred in reverse order from the English iron industry. While the Early Republic foundries were reluctant to switch to the more efficient coke fuel, they were more inclined to adopt the new puddling process for refining iron. The first puddling foundry in the United States was established in 1817 by Isaac Meason and Thomas Lewis in Smock, PA. Over the course of the next 20 years puddling foundries flourished near the iron deposits of New York, New Jersey, and Pennsylvania.

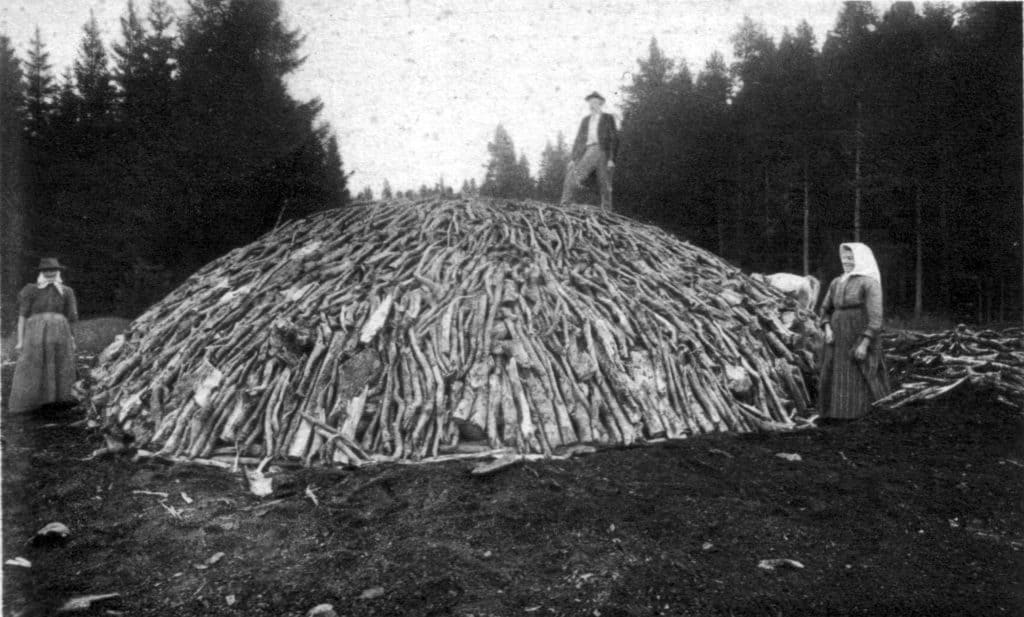

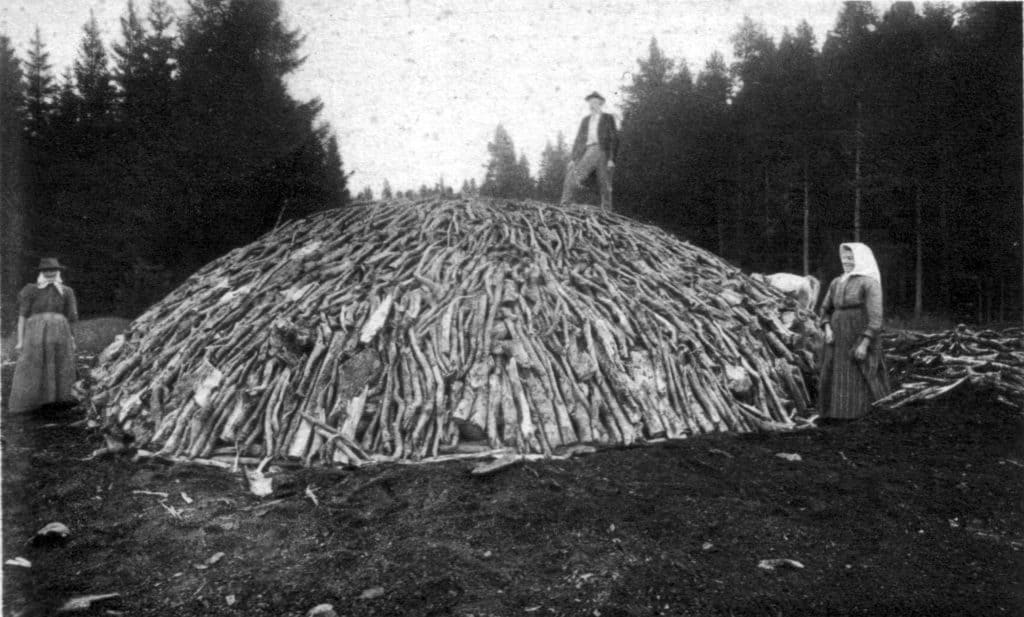

Wood pile before covering it with turf or soil, and firing it (circa 1890)

The new process made the furnaces more efficient and improved the quality of the iron. However, the foundries were still tied to the harvesting and processing of trees. This was a tedious process that required careful planning and diligent management. A foundry manager would need to arrange for the harvesting of a grove of trees a year or more in advance and then hire a crew to cut and haul the trees to a designated area so they could be converted to charcoal. The storage of the trees and the charcoal always carried the risk of a fire breaking out that could destroy months of fuel for the furnaces.

Early Use Of Coke In The American Iron Foundry

Coke was first introduced to the foundry process in the United States in 1827 at the Phoenix Iron Works in southeast Pennsylvania. The movement from charcoal was slow but steady. By 1840, when the Scranton brothers moved to Slocum’s Hollow to establish their iron forge, the use of coke in new foundries was a given. They chose a different method to heat their iron called the “hot blast method”. This method was developed in the 1820s in Scotland and seemed to solved the impurities issue that plagued the use of coke in iron production. This new method was faster and burned off the troublesome impurities that could affect the quality of the iron.

While the Scranton Brothers were experimenting with coke and straight coal to produce iron and steel, another family business was gearing up for bigger things. The Reeves and Whitaker Brothers had partnered together to start a foundry in the valley between Philadelphia and Reading thirteen years before. They had slowly built the business and were a commercial success. But the years leading to the Civil War would be more lucrative than they could have imagined. Changes were coming to eastern Pennsylvania that would expand the iron industry considerably.

Willman Industries Avoids The Potential Pitfalls Of Success

The iron industry has always been a place of determination, invention, and innovation. We understand those qualities because we have lived them out as a foundry for over one hundred years. It is a legacy that we will carry on for another one hundred years.

But the potential profits and personal gain have always been a temptation that has brought down even the savviest industrialist. We have seen many foundries overextend themselves and go out of business during the inevitable economic downturn. Their customers found that they couldn’t rely on them and found themselves in a sea of uncertainty. For this reason, Todd Willman, our president and CEO, likes to call Willman Industries a “safe haven foundry.”

What is a “safe haven foundry”?

Todd Willman explains it well:

“We make our living as a safe-haven foundry, providing highly engineered, high-quality castings with high levels of service. Most of our business has come to us because our competition could not make the quality or because our competition simply went out of business. Since Clay Willman bought the foundry in 1987, we have been profitable every year because we make our decisions based on what is best for the foundry for the next 40 years.”

“We make our living as a safe-haven foundry, providing highly engineered, high-quality castings with high levels of service. Most of our business has come to us because our competition could not make the quality or because our competition simply went out of business. Since Clay Willman bought the foundry in 1987, we have been profitable every year because we make our decisions based on what is best for the foundry for the next 40 years.”Being a “safe haven foundry” means that we are committed to principles and practices that will allow us to remain in business for the long-run. Willman Industries is one of few iron casting foundries to stay debt-free and actually grow in the recent years of recession. There is a reason new customers approach Willman Industries almost every day. It’s because those new clients know Willman Industries is a no-risk choice to manufacture their iron castings.

Choose Willman, Choose Quality

Contact us today to schedule a tour of our facilities or call us to discuss your part needs with our knowledgable staff. We guarantee you will not find a more diligent company or better quality parts. Choose Willman, choose quality!

But changes were happening in the iron industry around the world. In England, the smelting of iron using coke made from coal was first introduced in 1709. This important innovation expanded the opportunities for the iron industry in England and parts of Europe but wasn’t as urgent of a technological advance in other countries. Coke is a fuel source created when coal is heated in the absence of oxygen and coal was far more plentiful in England than wood. The English and Scottish foundries saw this as an opportunity for their countries to gain more independence from the foundries in continental Europe. The continental foundries, such as in Sweden and Russia, had the advantage of more abundant natural resources such as wood and plentiful rivers.

But changes were happening in the iron industry around the world. In England, the smelting of iron using coke made from coal was first introduced in 1709. This important innovation expanded the opportunities for the iron industry in England and parts of Europe but wasn’t as urgent of a technological advance in other countries. Coke is a fuel source created when coal is heated in the absence of oxygen and coal was far more plentiful in England than wood. The English and Scottish foundries saw this as an opportunity for their countries to gain more independence from the foundries in continental Europe. The continental foundries, such as in Sweden and Russia, had the advantage of more abundant natural resources such as wood and plentiful rivers. Coke was first introduced to the foundry process in the United States in 1827 at the Phoenix Iron Works in southeast Pennsylvania. The movement from charcoal was slow but steady. By 1840, when the Scranton brothers moved to Slocum’s Hollow to establish their iron forge, the use of coke in new foundries was a given. They chose a different method to heat their iron called the “hot blast method”. This method was developed in the 1820s in Scotland and seemed to solved the impurities issue that plagued the use of coke in iron production. This new method was faster and burned off the troublesome impurities that could affect the quality of the iron.

Coke was first introduced to the foundry process in the United States in 1827 at the Phoenix Iron Works in southeast Pennsylvania. The movement from charcoal was slow but steady. By 1840, when the Scranton brothers moved to Slocum’s Hollow to establish their iron forge, the use of coke in new foundries was a given. They chose a different method to heat their iron called the “hot blast method”. This method was developed in the 1820s in Scotland and seemed to solved the impurities issue that plagued the use of coke in iron production. This new method was faster and burned off the troublesome impurities that could affect the quality of the iron. “We make our living as a safe-haven foundry, providing highly engineered, high-quality castings with high levels of service. Most of our business has come to us because our competition could not make the quality or because our competition simply went out of business. Since Clay Willman bought the foundry in 1987, we have been profitable every year because we make our decisions based on what is best for the foundry for the next 40 years.”

“We make our living as a safe-haven foundry, providing highly engineered, high-quality castings with high levels of service. Most of our business has come to us because our competition could not make the quality or because our competition simply went out of business. Since Clay Willman bought the foundry in 1987, we have been profitable every year because we make our decisions based on what is best for the foundry for the next 40 years.”